Making regex from scratch in go

07 Branches

The OR expression

It’s very useful to use a regular expression to match against multiple different possible substrings. For example, to check that a file is an image type, you might use the regular expression "png|jpge|gif" on the file extension. This would tell you if the file was png OR jpeg OR gif. The options of the OR expression are determined by the separating them with a pipe symbol ("|").

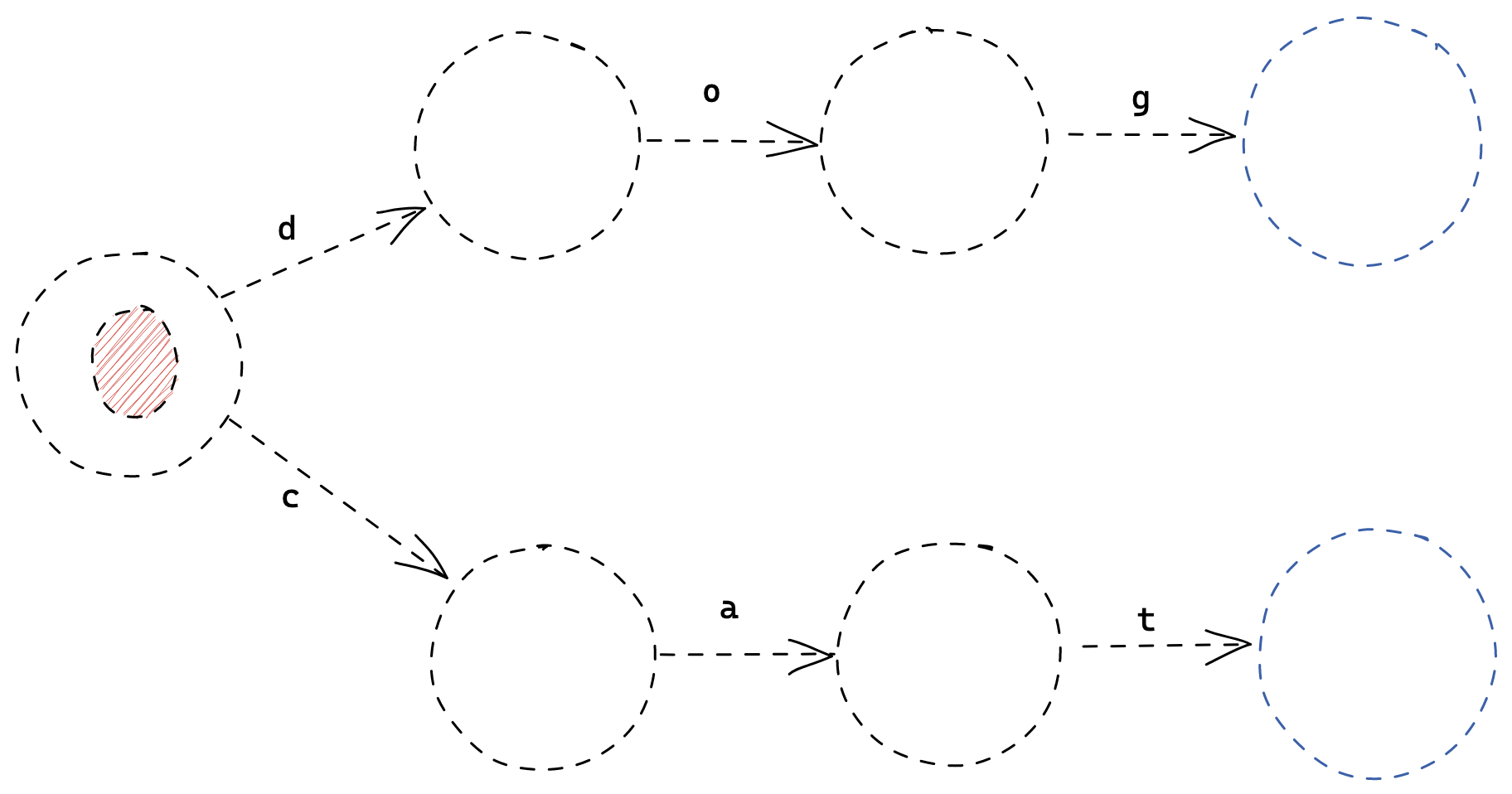

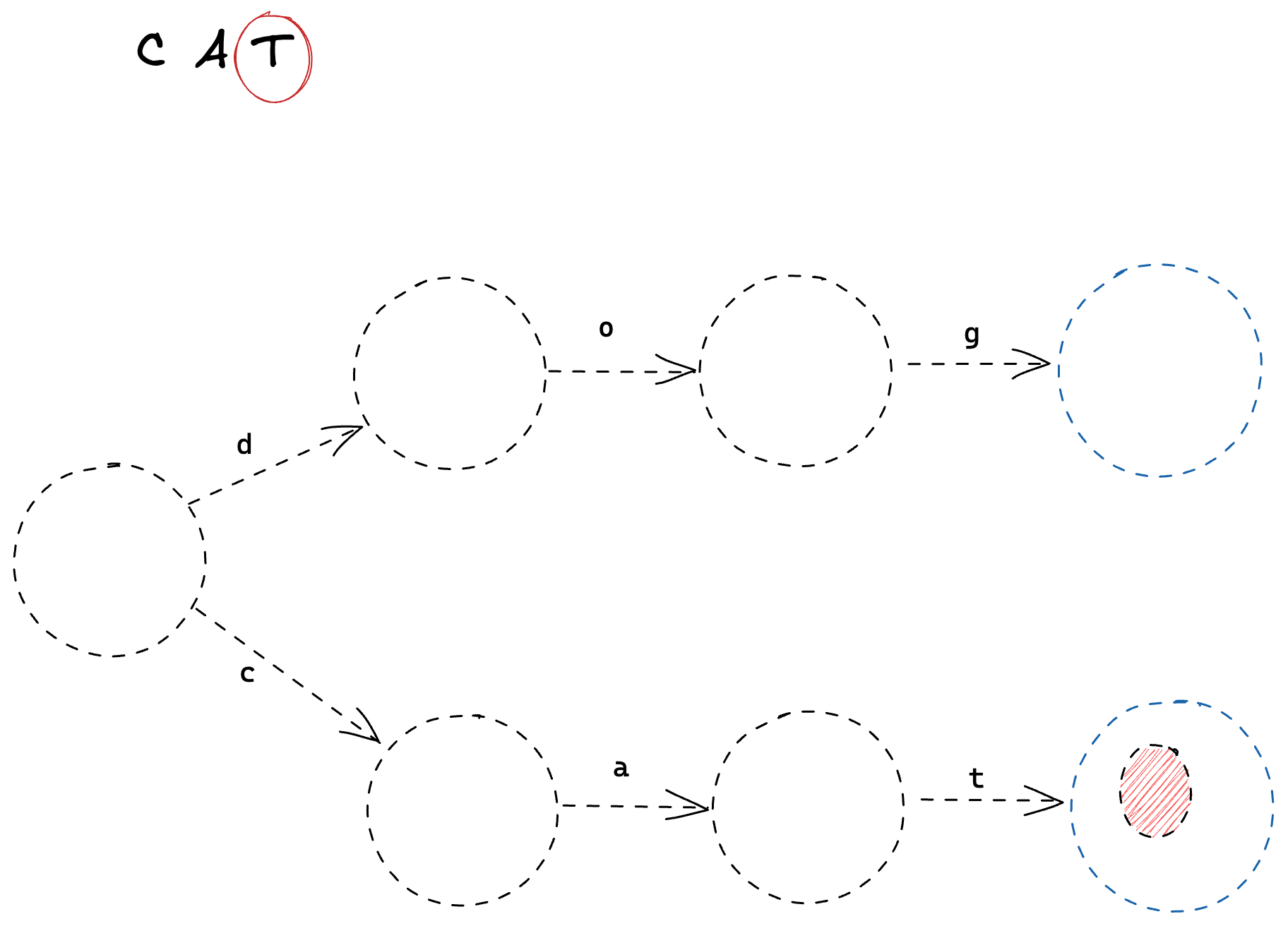

Let’s have a look at what an FSM would look like with OR expressions. Take the regular expression "dog|cat" as an example.

As we can see, it looks similar to our previous examples, with the notable difference that our starting state has multiple outward Transitions. In this case, it can transition on both the 'd' and the 'c' characters.

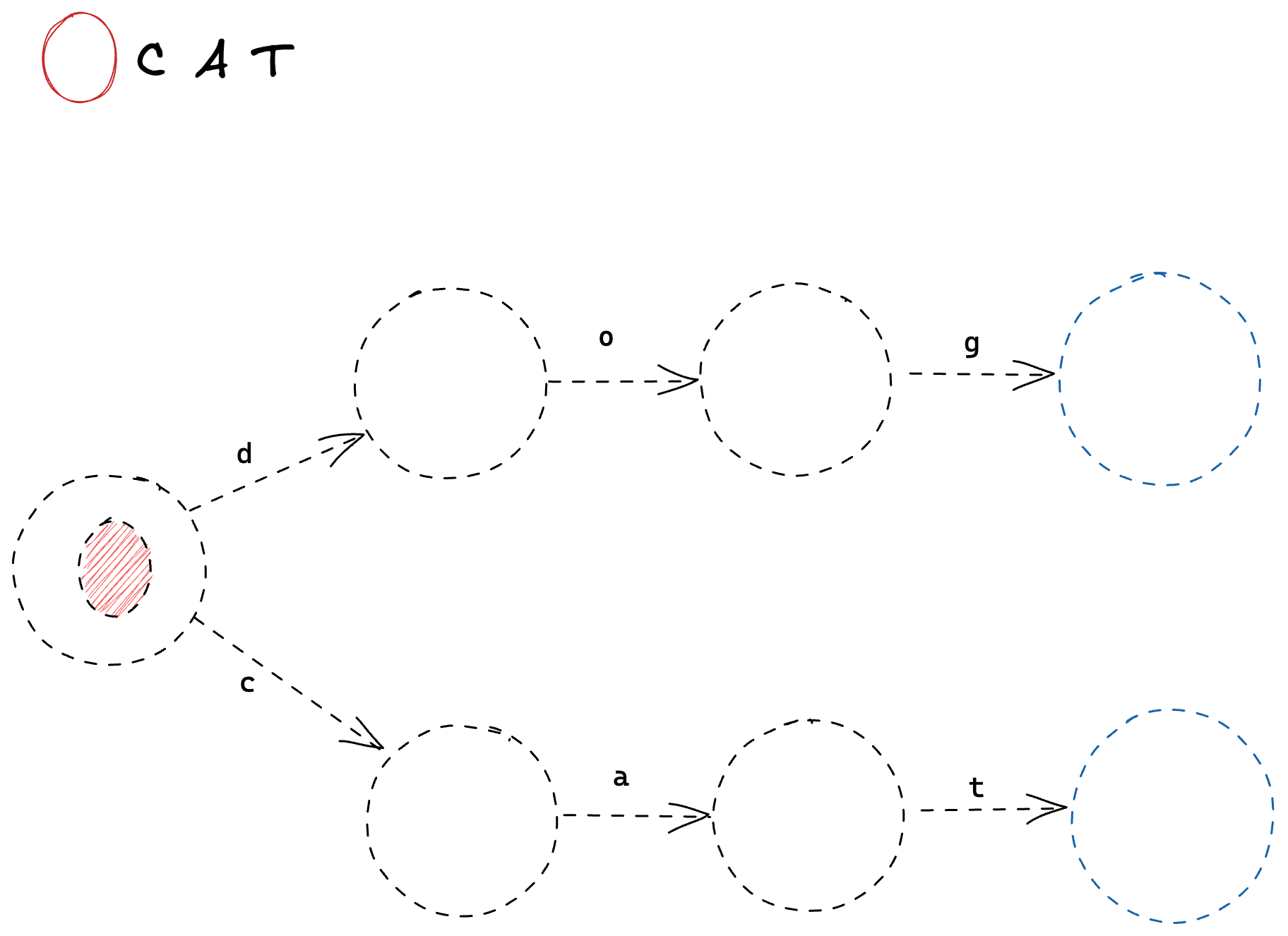

Let’s step through this using the string "cat" as our input search string.

First, we process the character 'c', which matches the bottom transition.

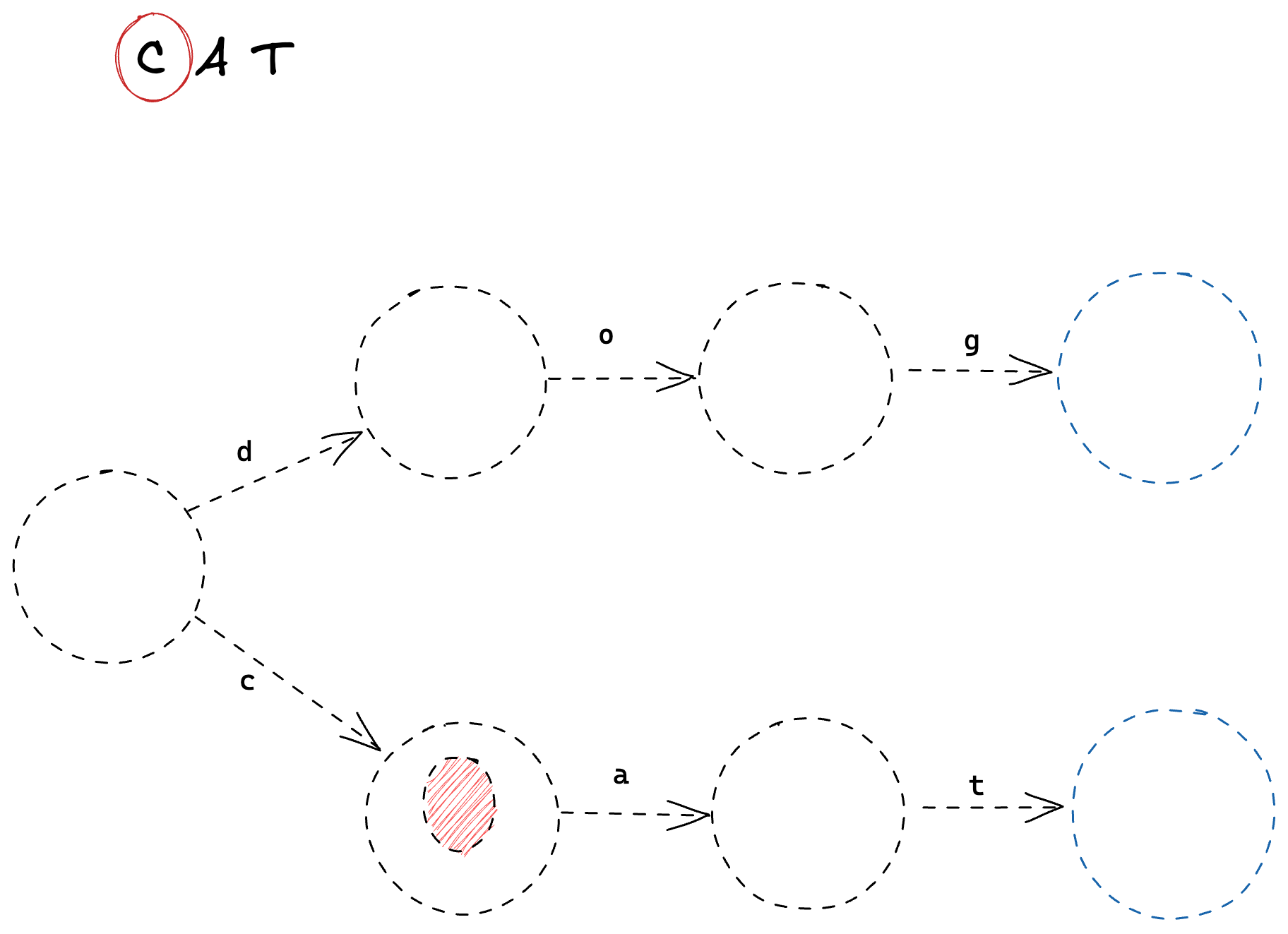

Then, we process 'a'

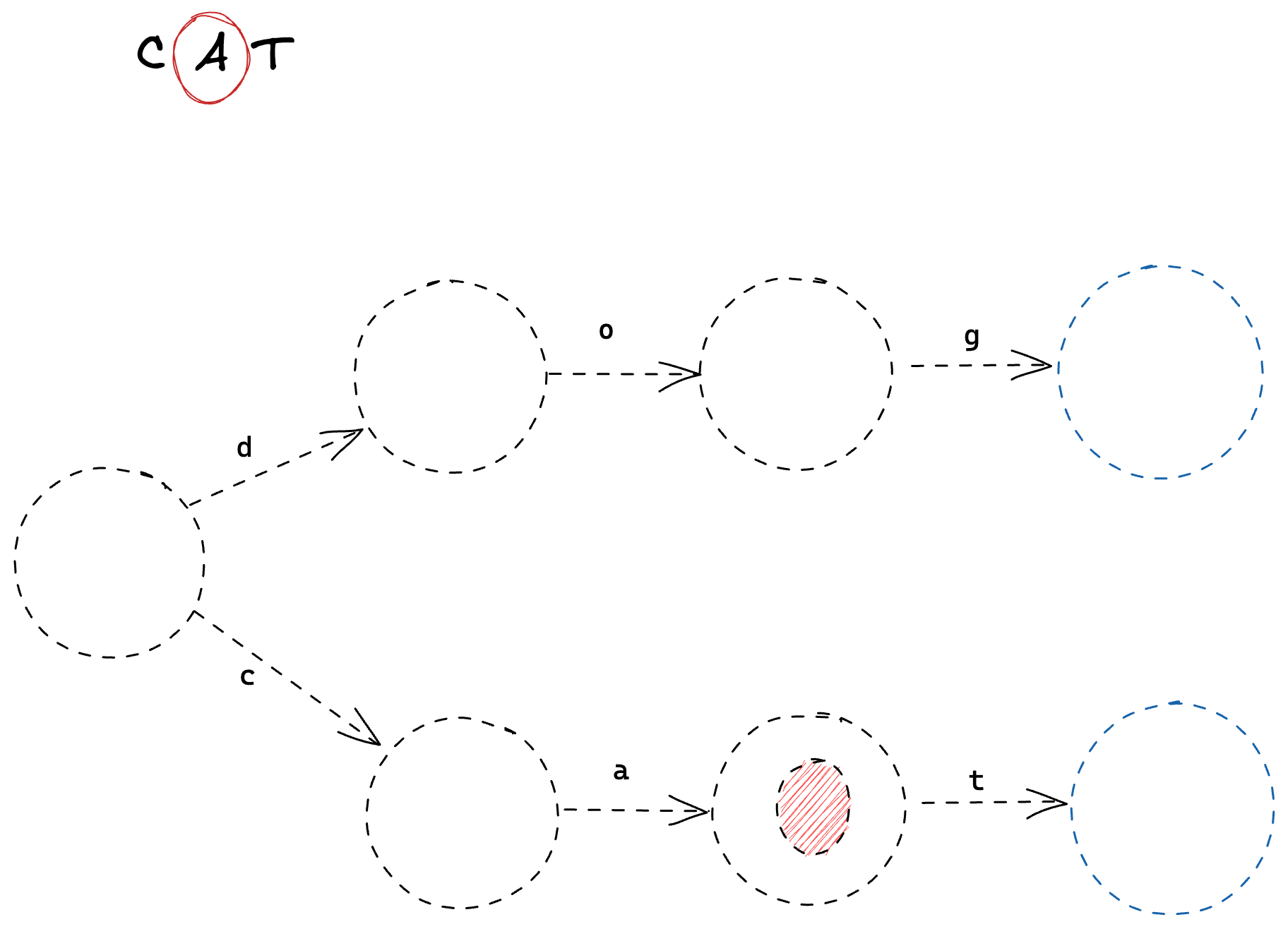

And finally 't', which leaves us in an end state.

Pretty simple stuff! Now that we know what we’re looking for, let’s start coding.

We’ll start at the Parser.

First, let’s add our data structures.

The Branch Data Structure

// ast.go

type Branch struct {

ChildNodes []Node

}

func (b *Branch) Append(node Node) {

panic("implement me")

}

func (b *Branch) compile() (head *State, tail *State) {

panic("implement me")

}

The structure of the Branch struct will be very similar to the Group struct - they both implement the CompositeNode interface and have child Nodes. The difference will be in how they are parsed, and how they are compiled.

Parsing Branch AST Nodes

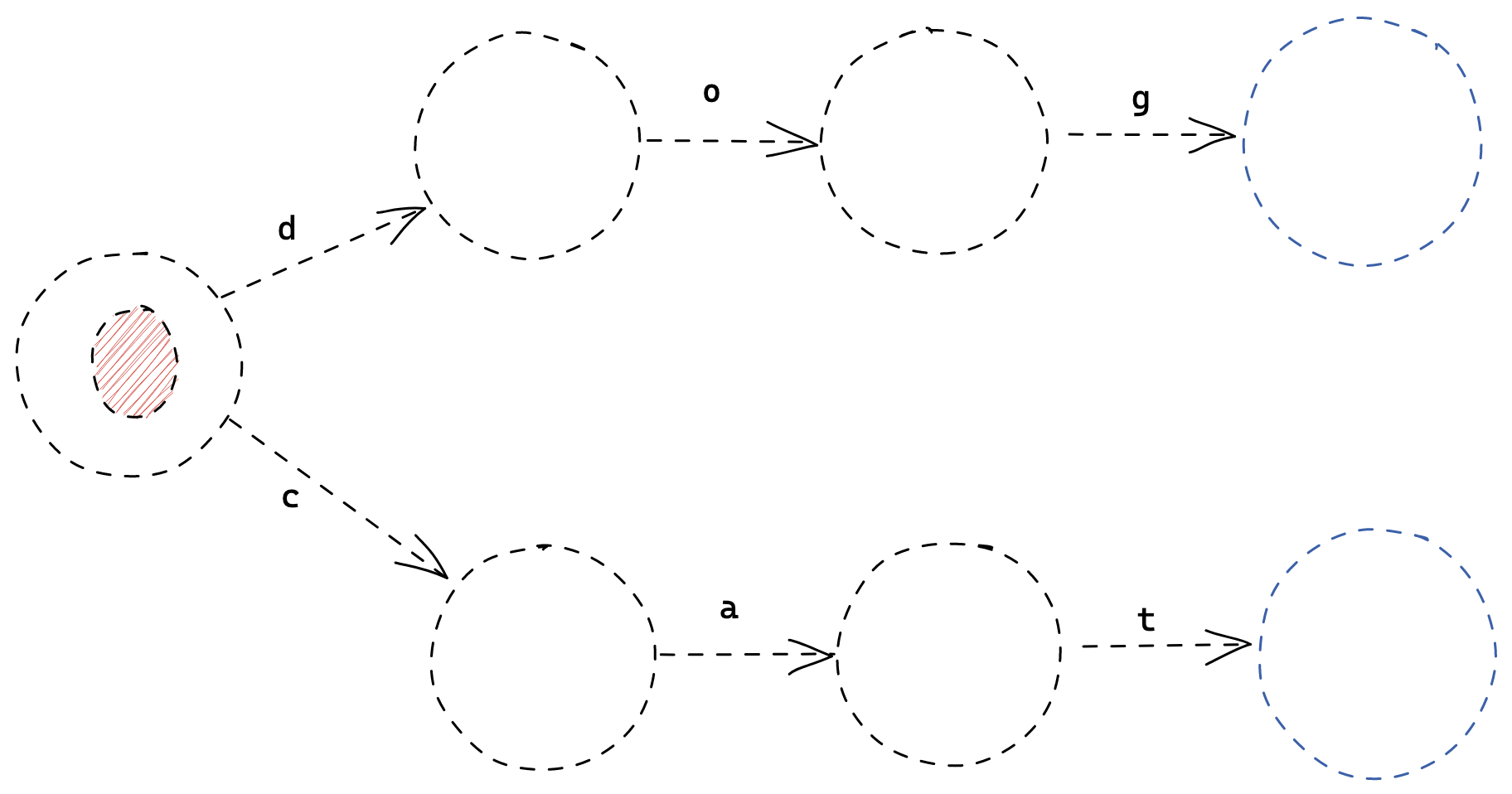

We’re going to want to be able to represent branches as AST nodes, so our parser needs to know how to take a regular expression such as cat|dog and turn it into a Branch AST node with two Group child nodes, each containing three CharacterLiteral nodes. Visually, the cat|dog example should look like this:

Let’s start by adding a test to our parser_test.go file.

@@ // parser_test.go

@@ func TestParser(t *testing.T) {

+ {name: "branches", input: "ab|cd|ef", expectedResult: &Branch{ChildNodes: []Node{

+ &Group{ChildNodes: []Node{

+ CharacterLiteral{Character: 'a'},

+ CharacterLiteral{Character: 'b'},

+ }},

+ &Group{ChildNodes: []Node{

+ CharacterLiteral{Character: 'c'},

+ CharacterLiteral{Character: 'd'},

+ }},

+ &Group{ChildNodes: []Node{

+ CharacterLiteral{Character: 'e'},

+ CharacterLiteral{Character: 'f'},

+ }},

+ }}},

}

Let’s run those tests and see what we’re working with. We get the following error message.

Expected [&{ChildNodes:[0x1400000c0d8 0x1400000c0f0 0x1400000c108]}], got [&{ChildNodes:[{Character:97} {Character:98} {Character:99} {Character:100 {Character:101} {Character:102}]}]

Hmm, not very helpful. The problem is that displaying hierarchical data structures is not something that Go does very well on it’s own. In this case, it’s just printing our pointers. We want something more like the tests we’ve just written - the indentation at each level makes it obvious which Nodes are child nodes and which are parent Nodes. Let’s take another quick detour and improve how we print out our AST Nodes.

Debug printing AST Nodes

We want each level in the hierarchy to be indented a bit more than the previous level, so that we end up with something like this:

level 1

level 2

level 3

level 2

level 2

level 1

We can do this by telling each node which level it is at, and having it print an indentation with the length of that level before it prints the description of the Node. Let’s start with the leaf nodes, as they’re the easiest.

// ast.go

func (l CharacterLiteral) string(indentation int) string {

padding := strings.Repeat("--", indentation)

return fmt.Sprintf("%sCharacterLiteral('%s')", padding, string(l.Character))

}

func (w WildcardLiteral) string(indentation int) string {

padding := strings.Repeat("--", indentation)

return fmt.Sprintf("%sWildcardCharacterLiteral", padding)

}

Now, the CompositeNodes, which for now is only Group, will also need to print it’s description with an indentation. The trick here is to also ask all of it’s child nodes to print with the indentation + 1.

// ast.go

func (g *Group) string(indentation int) string {

return compositeToString("Group", g.ChildNodes, indentation)

}

func (b *Branch) string(indentation int) string {

return compositeToString("Branch", b.ChildNodes, indentation)

}

func compositeToString(title string, children []Node, indentation int) string {

padding := strings.Repeat("--", indentation)

res := padding + title

for _, node := range children {

res += fmt.Sprintf("\n%s%s", padding, node.string(indentation+1))

}

return res

}

We’ll also need to tell Go that every node can print using the string(indentation int) method, so let’s add it to the Node interface.

@@ // ast.go

type Node interface {

compile() (head *State, tail *State)

+ string(indentation int) string

}

And finally call these methods from the composite Nodes String() method so that our tests use it for output.

// ast.go

func (g *Group) String() string {

return "\n" + g.string(1)

}

func (b *Branch) String() string {

return "\n" + b.string(1)

}

Now, let’s take a look at our error message again.

=== RUN TestParser/branches

parser_test.go:52: Expected:

--Branch

----Group

--------CharacterLiteral('a')

--------CharacterLiteral('b')

----Group

--------CharacterLiteral('c')

--------CharacterLiteral('d')

----Group

--------CharacterLiteral('e')

--------CharacterLiteral('f')

Got:

--Group

----CharacterLiteral('a')

----CharacterLiteral('b')

----CharacterLiteral('c')

----CharacterLiteral('d')

----CharacterLiteral('e')

----CharacterLiteral('f')

That’s better, we can now immediately see what’s going on.

It probably seems like we’re spending a lot of time building things to help us visualize our system, rather than building the system itself. That’s true, and this is a large investment. However, this should pay dividends when it comes to debugging issues that come up, and in simply understanding our system better. It’s hard to give hard numbers when it comes to deciding whether a tool is worth the time it takes to build it, but considering that the implementation is fairly straight forward, I think it’s easily worth it in this case.

So let’s fix our parser.

Adding Pipes to our Parser

During the parsing of a string of tokens, if we come across the Pipe ( '|') token, we want to do one of two things, depending on whether our root Node is a Branch node or not.

- If the root

Nodeis not aBranchnode, want to replace the root with a newBranchnode, which will contain the old rootNodeas its first child, and a newGroupas its second child. - If the root

Nodeis aBranchnode, we want to ‘split’ theBranch, which basically means adding a freshGroupnode as a child of theBranchnode.

Let’s walk through these in more detail.

1. Creating a new Branch node

let’s parse the regex "ab|cd".

First, the letter 'a'. It simply gets appended to our root Group node.

Then the same for 'b',

Now we have our pipe character '|'. With this, we should create a new Branch node and place our Group node as it’s first child. This Branch node will become the new root Node.

We should also create a new Group node, and it should be a new child of the Branch node.

We should end up with the following;

Continuing, we have 'c'. We should now be appending new expressions to the newly created group (the second child of the root Branch node).

And finally, 'd' is also added to the last child of the root Branch node. The AST parsing is now complete.

2. Splitting a branch

Let’s try parsing the regex a|b|c.

First, we parse the 'a' character. It gets added to the root Group node.

Now, our first '|' token. This uses the first option, where a new Branch is created and set as the root Node.

Next, an 'b' character token. This will be appended to the last child of Branch.

And now, our second '|' token. As the root is now a Branch node, we will ‘split’ this branch and create a new child with a fresh Group node.

And finally, the 'c' character will be appended to the newly created Group node.

Coding the Pipe Parser

The changes necessary for this are actually quite small. We simply need to add our Branch node and a new case in the parsers main switch statement.

First, our Branch node.

// ast.go

type Branch struct {

ChildNodes []Node

}

func (b *Branch) Append(node Node) {

for i := len(b.ChildNodes) - 1; i > 0; i-- {

switch n := b.ChildNodes[i].(type) {

case CompositeNode:

n.Append(node)

return

}

}

panic("should have at least one composite node child")

}

func (b *Branch) compile() (head *State, tail *State) {

panic("implement me")

}

The Append method here is interesting. We want to append to the latest child of the Branch, so we iterate backwards through the ChildNodes. We also expect that we will always have at least one CompositeNode child, so we should panic otherwise.

Also, we add a stand-in compile function to get the compiler to stop complaining.

We also need a way to ‘split’ the branch. This simply means adding a new child with an empty Group node.

// ast.go

func (b *Branch) Split() {

b.ChildNodes = append(b.ChildNodes, &Group{})

}

And then, in our parser, we add a case for processing Pipe tokens.

@@ // parser.go

func (p *Parser) Parse() Node {

- root := Group{}

+ var root CompositeNode

+ root = &Group{}

for _, t := range p.tokens {

switch t.symbol {

case Character:

root.Append(CharacterLiteral{Character: t.letter})

case AnyCharacter:

root.Append(WildcardLiteral{})

+ case Pipe:

+ switch b := root.(type) {

+ case *Branch:

+ b.Split()

+ default:

+ root = &Branch{ChildNodes: []Node{root, &Group{}}}

+ }

}

}

- return &root

+ return root

}

Notice that our root Node now has to be of the interface type CompositeNode, as it can now be either a Group or a Branch type.

This should be enough to get our Parser tests green again. Next, we need to compile this AST node into an FSM.

Compiling a Branch node

We want to take our AST and create a valid FSM from it. This will be enough to make our implementation work, so let’s start with a test before we implement anything.

@@ // fsm_test.go

@@ func TestFSMAgainstGoRegexPkg(t *testing.T) {

{"wildcard regex matching", "ab.", "abc"},

{"wildcard regex not matching", "ab.", "ab"},

{"wildcards matching newlines", "..0", "0\n0"},

+

+ // branch

+ {"branch matching 1st branch", "ab|cd", "ab"},

+ {"branch matching 2nd branch", "ab|cd", "cd"},

+ {"branch not matching", "ab|cd", "ac"},

}

These should be failing as we simply panic when we try to compile any Branch AST Nodes. Let’s fix this.

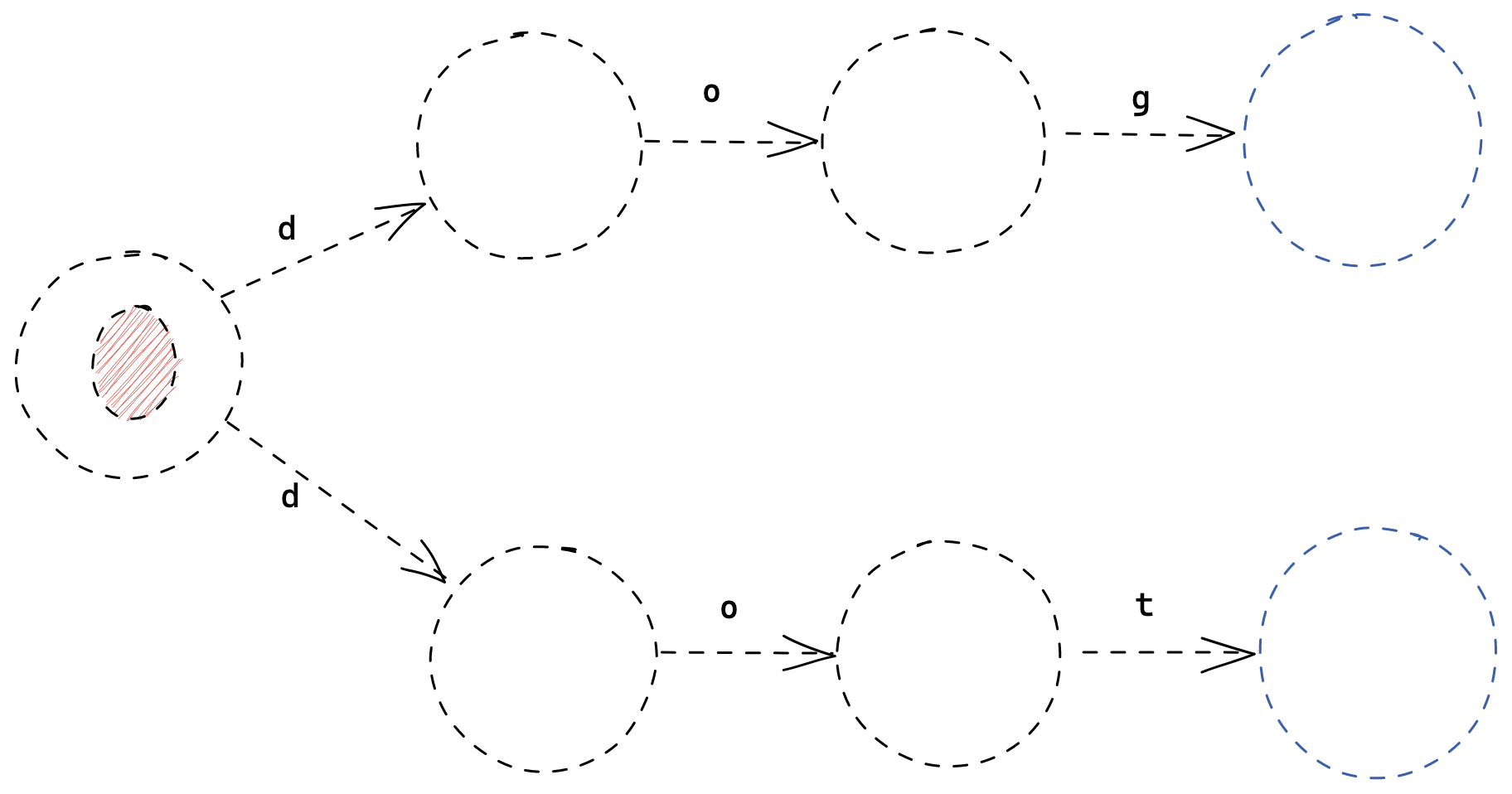

Going from this:

To this:

Is not too difficult. They already share a lot of the same characteristics because the shape is so similar. As I’ve stressed in earlier chapters, parsing the structure first and then compiling the end result separately is a fantastic way to reduce the overall complexity of this operation.

For now, we can use the following algorithm for parsing a Branch node:

- Create a starting

State. - Compile each child node, and merge the first

Stateof each child with the startingState.

This has some issues, as we’ll see later, but for now this will work. Let’s put it into code.

// ast.go

func (b *Branch) compile() (head *State, tail *State) {

// 1. Create a starting State.

startState := &State{}

// 2. Compile each child node, and merge the first State of each child with the starting State.

for _, expression := range b.ChildNodes {

nextStateHead, _ := expression.compile()

startState.merge(nextStateHead)

}

return startState, startState

}

That should be enough to successfully compile a Branch node. Our tests should now be green, so let’s see what we’ve created by using our visualizer tools.

Let’s see what happens when we run the draw "ab|cd|ef" "aaccef" command. We should get something like the following in the browser.

v6-branching-incomplete draw "ab|cd|ef" "aaccef"Looks great! Our FSM looks exactly as we’d expect, and our algorithm (after quite a bit of backtracking) eventually finds the correct match.

There is one deep dark problem here though which we’ve been conveniently ignoring, and it goes right to the heart of finite state machines.

Deterministic vs Non-Deterministic

Our examples up until now have all worked fine because they have one thing in common; every State has only one transition for each character in the alphabet. Because of this, we know exactly which state will be red after we process a character. What happens if we get rid of this invariant? How can our FSM behave?

Consider the following FSM for the regular expression dog|dot:

We can condense the problem into an even simpler FSM:

If we process the character 'a', what should happen? Should we go State 1 or to State 2? Or should we go to both?

The answer to this question is the difference between a Deterministic Finite State Automata (DFA) and a Non-Deterministic Finite State Automata (NFA).

A DFA cannot have more than one transition with the same character from a single state. It requires that only a single state can be active at any time, and that once a state is processed with a character, we know deterministically in which state we will be in afterwards.

In an NFA, there is no such restriction. If there are multiple possible transitions for a given character, both states can be examined. One can imagine this as either multiple states being active on an FSM, or multiple FSMs being traversed in parallel. The result is the same.

Up until now, we have been using a DFA. Now we’re going to change our model to an NFA in order to be able to process the type of FSM I’ve shown above.

Changing to a NFA model

First, let’s add a test which illustrates our issue.

@@ fsm_test.go

@@ func TestFSMAgainstGoRegexPkg(t *testing.T) {

{"wildcard regex matching", "ab.", "abc"},

{"wildcard regex not matching", "ab.", "ab"},

{"wildcards matching newlines", "..0", "0\n0"},

// branch

{"branch matching 1st branch", "ab|cd", "ab"},

{"branch matching 2nd branch", "ab|cd", "cd"},

{"branch not matching", "ab|cd", "ac"},

+ {"branch with shared characters", "dog|dot", "dog"}, // will work

+ {"branch with shared characters", "dog|dot", "dot"}, // will not work

}

So, from our tests we can see that we will find dog, but not dot. Let’s take a look at our visualizer to understand why.

v6-branching-incomplete draw "dog|dot" "dog"So, when searching for "dog", we travel through the upper branch and successfully find a match. Nothing surprising here. Let’s look at "dot".

v6-branching-incomplete draw "dog|dot" "dot"Ah… when matching the first 'd' character, we go up the same branch as before. How can the program know which branch it should follow? As it can’t see into the future, there are two possibilities.

- Backtracking

- Parallel States

Backtracking would mean travelling backwards to the route of the branch in the case of failure, then trying the next Transition for the 'd' character. We can think of this as a form of Depth First Search as we optimistically explore the first branch, then go back in the case of failure.

Parallel States would mean going down all the possible branches simultaneously, exploring every state for which there is a valid Transition. You can think of this as a Breadth First Search of the FSM.

We’re going to be exploring the second option in our program.

Parallel States

We’re introducing a large change into how our algorithm works. Instead of simply tracking a single State, we will now track a set of States. Processing a character will now mean looking at all active States and their valid Transitions, and using those as the next active States. We’ll also need to modify our visualisation code to color multiple active States.

As tracking the active State is the responsibility of the runner, let’s start there.

@@ // runner.go

type runner struct {

- head *State

- current *State

+ head *State

+ activeStates Set[*State]

}

func NewRunner(head *State) *runner {

r := &runner{

- head: head,

- current: head,

+ head: head,

+ activeStates: NewSet[*State](head),

}

return r

}

func (r *runner) Reset() {

- r.current = r.head

+ r.activeStates = NewSet[*State](r.head)

+}

We no longer want to track a single *State, but instead a set of *State. We’ve used a generic Set object here, let’s define it.

// set.go

type Set[t comparable] map[t]struct{}

func NewSet[t comparable](items ...t) Set[t] {

set := Set[t](make(map[t]struct{}))

for _, item := range items {

set.add(item)

}

return set

}

func (s *Set[t]) add(item t) {

(*s)[item] = struct{}{}

}

func (s *Set[t]) remove(item t) {

delete(*s, item)

}

func (s *Set[t]) has(item t) bool {

_, ok := (*s)[item]

return ok

}

func (s *Set[t]) list() []t {

set := *s

list := make([]t, len(set))

i := 0

for item := range set {

list[i] = item

i++

}

return list

}

func (s *Set[t]) size() int {

return len(*s)

}

The Set type is more or less a wrapper around the map[t]struct{}, which should make things a bit easier.

Lots of things in runner should now be broken - this is normal as we’ve completely ripped out the underlying data structure. Our algorithm is going to change significantly. First let’s look at the Next(input rune) method.

As we mentioned before, we should now generate a new set of States by evaluating the transitions of the active States. If there are no active States, we should simply return.

@@ // runner.go

func (r *runner) Next(input rune) {

- if r.current == nil {

+ if r.activeStates.size() == 0 {

return

}

- // move to next matching transition

- r.current = r.current.firstMatchingTransition(input)

+ nextActiveStates := Set[*State]{}

+ for activeState := range r.activeStates {

+ for _, nextState := range activeState.matchingTransitions(input) {

+ nextActiveStates.add(nextState)

+ }

+ }

+ r.activeStates = nextActiveStates

}

One thing to notice here is that we now use a different method on the State type; matchingTransitions(input rune) instead of firstMatchingTransition(input rune). This should return a list of States instead of a single State. Let’s define that next.

@@ // state.go

-func (s *State) firstMatchingTransition(input rune) *State {

+func (s *State) matchingTransitions(input rune) []*State {

+ var res []*State

for _, t := range s.transitions {

if t.predicate.test(input) {

- return t.to

+ res = append(res, t.to)

}

}

-

- return nil

+ return res

}

The difference here is subtle, but significant. All matching States are returned here, not just the first one we find.

Going back to our runner, we also need a new way of determining if the runner status. Instead of checking for a single active State, we need to check all of the active States and return if any are success States.

@@ // runner.go

func (r *runner) GetStatus() Status {

- // if the current state is nil, return Fail

- if r.current == nil {

+ // if there are no actives states, return Fail

+ if r.activeStates.size() == 0 {

return Fail

}

- // if the current state has no transitions from it, return Success

- if r.current.isSuccessState() {

- return Success

+ // if any of the active states is a success state, return Success

+ for state := range r.activeStates {

+ if state.isSuccessState() {

+ return Success

+ }

}

// else, return normal

return Normal

}

That should be enough to solve our current problem and bring our tests back to green!

It’s useful at this point to go back and revisit our visualisation tools. We no longer draw a single active state, so let’s update our drawSnapshot function to draw each of the active States.

@@ // draw.go

func (r runner) drawSnapshot() string {

graph, nodeSet := r.head.Draw()

- switch r.GetStatus() {

- case Normal:

- graph += fmt.Sprintf("\nstyle %d fill:#ff5555;", nodeSet.getIndex(r.current))

- case Success:

- graph += fmt.Sprintf("\nstyle %d fill:#00ab41;", nodeSet.getIndex(r.current))

+ activeStates := getSortedActiveStates(r.activeStates.list(), nodeSet)

+

+ for _, state := range activeStates {

+ nodeLabel := nodeSet.getIndex(state)

+ if state.isSuccessState() {

+ graph += fmt.Sprintf("\nstyle %d fill:#00ab41;", nodeLabel)

+ } else {

+ graph += fmt.Sprintf("\nstyle %d fill:#ff5555;", nodeLabel)

+ }

}

return graph

}

+func getSortedActiveStates(activeStates []*State, nodeSet OrderedSet[*State]) []*State {

+ byAscendingNodeLabel := func(i, j int) bool {

+ return nodeSet.getIndex(activeStates[i]) < nodeSet.getIndex(activeStates[j])

+ }

+ sort.Slice(activeStates, byAscendingNodeLabel)

+ return activeStates

+}

While not strictly necessary, it’s useful to sort the States by their label to make it deterministic (iterating over a map in Go uses a random order).

With those changes, let’s take a look at our previous example in our visualizer.

v6-parallel-incomplete draw "dog|dot" "dot"Look at that! We now ‘split’ our State processing and traverse all possible States at the same time.

We could leave it there, but this is a nice opportunity to make an optimization. Before we carry out that optimization, let’s look at one more example.

v6-parallel-incomplete draw "aab|aac|aad" "aaaab"We end up in with the right answer here because we’re backtracking across every substring of the search string "aaaab". This was necessary when we were an DFA, and we could only track one State at a time. However, now we’re a NFA there’s no need to backtrack and reprocess the input once we hit a failure - we can instead do the same processing in parallel.

In order to process each substring in parallel, we need to activate the starting State when we process each character.

Let’s make a method in the runner to activate the first state. We’ll call this Start() for now.

// runner.go

func (r *runner) Start() {

r.activeStates.add(r.head)

}

As we’re going to change our algorithm, we expect that our visualisations will change also, so let’s modify those tests to verify the behaviour. First, let’s change our test to use the Start method after every character.

@@ // draw_test.go

@@ func Test_DrawSnapshot(t *testing.T) {

for _, tt := range tests {

t.Run(tt.name, func(t *testing.T) {

runner := NewRunner(tt.fsmBuilder())

for _, char := range tt.input {

runner.Next(char)

+ runner.Start()

}

snapshot := runner.drawSnapshot()

if !reflect.DeepEqual(tt.expected, snapshot) {

t.Fatalf("Expected drawing to be \n\"%v\"\ngot\n\"%v\"", tt.expected, snapshot)

}

})

}

And then let’s change our test expectations so that the previous States are also highlighted.

@@ // draw_test.go

@@ func Test_DrawSnapshot(t *testing.T) {

tests := []test{

{

name: "initial snapshot",

fsmBuilder: abcBuilder,

input: "",

expected: `graph LR

0((0)) --"a"--> 1((1))

1((1)) --"b"--> 2((2))

2((2)) --"c"--> 3((3))

style 3 stroke:green,stroke-width:4px;

style 0 fill:#ff5555;`,

},

{

name: "after a single letter",

fsmBuilder: abcBuilder,

input: "a",

expected: `graph LR

0((0)) --"a"--> 1((1))

1((1)) --"b"--> 2((2))

2((2)) --"c"--> 3((3))

style 3 stroke:green,stroke-width:4px;

+style 0 fill:#ff5555;

style 1 fill:#ff5555;`,

},

{

- name: "last state highlighted",

+ name: "all states highlighted",

fsmBuilder: aaaBuilder,

input: "aaa",

expected: `graph LR

0((0)) --"a"--> 1((1))

1((1)) --"a"--> 2((2))

2((2)) --"a"--> 3((3))

style 3 stroke:green,stroke-width:4px;

+style 0 fill:#ff5555;

+style 1 fill:#ff5555;

+style 2 fill:#ff5555;

style 3 fill:#00ab41;`,

},

}

All that’s left to do is make changes to our match function of the myRegex type. The changes here are simple; we want to Start the runner again after every character is processed so that every substring is processed, and we no longer want to recursively call the function again on a substring in the case of failure.

@@ // regex.go

func match(runner *runner, input []rune, debugChan chan debugStep, offset int) bool {

runner.Reset()

if debugChan != nil {

debugChan <- debugStep{runnerDrawing: runner.drawSnapshot(), currentCharacterIndex: offset}

}

for i, character := range input {

runner.Next(character)

+ runner.Start()

if debugChan != nil {

debugChan <- debugStep{runnerDrawing: runner.drawSnapshot(), currentCharacterIndex: offset + i + 1}

}

status := runner.GetStatus()

- if status == Fail {

- return match(runner, input[1:], debugChan, offset+1)

- }

-

if status == Success {

return true

}

With all that in place, let’s try it again.

v6 draw "aab|aac|aad" "aaaab"Now, all States are active most of the time because the initial state is being activated on every new character, meaning that each substring is being processed through the FSM. This means that no backtracking is necessary.

It looks like we’re pretty close to a full implementation of the'|' character in regular expressions. Let’s fire up our fuzzer and see if it can find what we’re missing.

@@ // fsm_test.go

@@ func FuzzFSM(f *testing.F) {

f.Fuzz(func(t *testing.T, regex, input string) {

- if strings.ContainsAny(regex, "[]{}$^|*+?\\") {

+ if strings.ContainsAny(regex, "[]{}$^*+?\\") {

Hmm, we do see an error.

--- FAIL: FuzzFSM (0.00s)

fsm_test.go:137: Mismatch -

Regex: '|1' (as bytes: 7c31),

Input: '0' (as bytes: 30)

->

Go Regex Pkg: 'true',

Our regex result: 'false'

It seems that we return false when a regex is empty on one side of the Pipe expression, when we should return true. Let’s see if we can see what’s going on from the FSM graph for '|1'

Our compiled FSM looks as follows;

Well, that’s clearly not correct. We actually need an FSM which instantly matches, because we’re saying that it should match the regex '1' OR match the regex '' (the empty string), which everything should match.

We’re going to do this with a useful trick for handling the empty string regular expression called epsilons.

Check out this part of the project on GitHub here

Previous: 06 Pretty Vizualizations

Next: 08 Epsilons