Making regex from scratch in go

04 Testing, Fuzzing, and fixing things

We can spend some time here doing some interesting things to our tests, which should make our lives a bit easier down the road.

Testing against the Go regex package

As Go includes its own regex package, we can use this to validate our own implementation by providing them with the same input and comparing the results.

First, let’s create our own regex package with the same method as the Go package, MatchString(). We’ll call this package myRegex to differentiate it.

// regex.go

type myRegex struct {

fsm *State

}

func NewMyRegex(re string) *myRegex {

tokens := lex(re)

parser := NewParser(tokens)

ast := parser.Parse()

state, _ := ast.compile()

return &myRegex{fsm: state}

}

func (m *myRegex) MatchString(input string) bool {

runner := NewRunner(m.fsm)

for _, character := range input {

runner.Next(character)

}

return runner.GetStatus() == Success

}

All we’re doing here is setting up our Lexer, Parser, Compiler and Runner, then running through each character in the input. After running through the input string, we return the status.

Now, let’s add a test which compares the results from our own FSM and the Go regex library.

// fsm_test.go

func TestFSMAgainstGoRegexPkg(t *testing.T) {

type test struct {

name string

regex string

input string

}

tests := []test{

{"empty string", "abc", ""},

{"non matching string", "abc", "xxx"},

{"matching string", "abc", "abc"},

{"partial matching string", "abc", "ab"},

}

for _, tt := range tests {

t.Run(tt.name, func(t *testing.T) {

compareWithGoStdLib(t, NewMyRegex(tt.regex), tt.regex, tt.input)

})

}

}

func compareWithGoStdLib(t *testing.T, myRegex *myRegex, regex, input strin

g) {

t.Helper()

result := myRegex.MatchString(input)

goRegexMatch := regexp.MustCompile(regex).MatchString(input)

if result != goRegexMatch {

t.Fatalf(

"Mismatch - \nRegex: '%s' (as bytes: %x), \nInput: '%s' (as byt

es: %x) \n-> \nGo Regex Pkg: '%t', \nOur regex result: '%v'",

regex,

[]byte(regex),

input,

[]byte(input),

goRegexMatch,

result,

)

}

}

Our tests should still be green. We can now remove our old tests.

@@ // fsm_test.go

-func TestCompiledFSM(t *testing.T) {

Let’s compare the test structs between this and our previous tests.

// old tests

type test struct {

name string

input string

expectedStatus Status

}

// new tests

type test struct {

name string

regex string

input string

}

Notice that we no longer require the Status field. This is because we no longer need to specify the result, as the Go library does that for us!

Adding a new test case is pretty simple, we just need the inputs and the test is ready to go;

@@ // fsm_test.go

tests := []test{

{"empty string", "abc", ""},

{"non matching string", "abc", "xxx"},

{"matching string", "abc", "abc"},

{"partial matching string", "abc", "ab"},

+ {"nested expressions", "a(b(d))c", "abdc"},

}

Having a way of automatically computing the desired output for a test not only makes writing the tests less work, but also open up some interesting possibilities, such as Fuzzing.

Fuzzing

Go 1.18 introduced fuzzing to its standard library, which is an automated way of barraging your code with semi-random input to try to find hidden errors.

Let’s write a simple fuzz test.

// fsm_test.go

func FuzzFSM(f *testing.F) {

f.Add("abc", "abc")

f.Add("abc", "")

f.Add("abc", "xxx")

f.Add("ca(t)(s)", "dog")

f.Fuzz(func(t *testing.T, regex, input string) {

_, err := regexp.Compile(regex)

if err != nil {

t.Skip()

}

compareWithGoStdLib(t, NewMyRegex(regex), regex, input)

})

}

Let’s step through this a bit. First, we need to add a few examples of input to our test function so that Go can seed the test corpus.

// fsm_test.go

f.Add("abc", "abc")

f.Add("abc", "")

f.Add("abc", "xxx")

f.Add("ca(t)(s)", "dog")

Now for the test function;

// fsm_test.go

f.Fuzz(func(t *testing.T, regex, input string) {

_, err := regexp.Compile(regex)

if err != nil {

t.Skip()

}

compareWithGoStdLib(t, NewMyRegex(regex), regex, input)

})

First, we only want to test valid regex statements, so any invalid statements we can simply ignore.

// fsm_test.go

_, err := regexp.Compile(regex)

if err != nil {

t.Skip()

}

After that, we can simply test in the same way as in our previous test using compareWithGoStdLib().

Let’s see what happens when we run this fuzz test. Use the following command line instruction;

go test ./src/v3/... -fuzz ^FuzzFSM$

Your path might be different, use the path of the package with the test and FSM implementation.

We found an error!

Let’s get a’fixing

Your mileage may vary. Go fuzzing uses randomised input, so there’s no guarantee that errors will show up in the same order as I show here.

➜ search git:(master) ✗ go test ./src/v3/... -fuzz ^FuzzFSM$

fuzz: elapsed: 0s, gathering baseline coverage: 0/1110 completed

failure while testing seed corpus entry: FuzzFSM/08fa440d20a250cf53d6090f036f15915901b50eb6d2958bb4b00ce71de7ec7a

fuzz: elapsed: 0s, gathering baseline coverage: 3/1110 completed

--- FAIL: FuzzFSM (0.21s)

--- FAIL: FuzzFSM (0.00s)

v3_test.go:106: Mismatch -

Regex: 'aA' (as bytes: 6141),

Input: '̇aaA' (as bytes: 616141)

->

Go Regex Pkg: 'true',

Our regex result: 'false'

Problem 1

It seems that passing aaA to the regex aA fails for our implementation, but passes for the Go implementation. This makes sense, because the Go regex package MatchString method we’re using will look for a match anywhere in the string, whereas we’re looking only at the beginning of the string.

Before we fix this, let’s add a test for this case.

@@ // fsm_test.go

{"non matching string", "abc", "xxx"},

{"matching string", "abc", "abc"},

{"partial matching string", "abc", "ab"},

{"nested expressions", "a(b(d))c", "abdc"},

+ {"substring match with reset needed", "aA", "aaA"},

Now let’s modify our test function to reset our FSM if there is a failure. That way, we will find matches at any point in the string, not just the beginning.

@@ // regex.go

func (m *myRegex) MatchString(input string) bool {

runner := NewRunner(m.fsm)

for _, character := range input {

runner.Next(character)

+ status := runner.GetStatus()

+ if status == Fail {

+ runner.Reset()

+ runner.Next(character)

+ continue

+ }

+

+ if status != Normal {

+ return status

+ }

}

return runner.GetStatus() == Success

}

Notice that we need to run runner.Next(character) after the reset because the second a in the input string needs to be used in the second attempt. More on that later.

Let’s run the fuzzer again.

Problem 2

v3_test.go:126: Mismatch -

Regex: '' (as bytes: ),

Input: '̇A' (as bytes: 41)

->

Go Regex Pkg: 'true',

Our regex result: 'false'

This time the issue is when the regex is an empty string. In these cases, any input should match. Let’s write a test case.

// fsm_test.go

{"empty string", "abc", ""},

+ {"empty regex", "", "abc"},

{"non matching string", "abc", "xxx"},

And now we can solve this by adding a check in our matchRegex function;

@@ // regex.go

func (m *myRegex) MatchString(input string) bool {

runner := NewRunner(m.fsm)

+ // for empty regex

+ if runner.GetStatus() == Success {

+ return true

+ }

for _, character := range input {

runner.Next(character)

status := runner.GetStatus()

if status == Fail {

runner.Reset()

runner.Next(character)

continue

}

if status != Normal {

return status

}

}

return runner.GetStatus() == Success

}

Why does this work? In the case of an empty regex, the compiler would produce a single state FSM. As the FSM will have no outbound transitions, this will function as an end state. So, for an empty regex, we just need to check the status before we do any processing.

Tests are green so back to the fuzzer.

Problem 3

v3_test.go:105: Mismatch - Regex: '.', Input: '' -> Go Regex Pkg: 'false', Our regex result: 'success'

We’re now failing when using the regex . and an input string. This makes sense because we haven’t implemented the wildcard character . (yet). For now, let’s ignore these special characters in our fuzz tests.

@@ // fsm_test.go

f.Fuzz(func(t *testing.T, regex, input string) {

+ if strings.ContainsAny(regex, "[]{}$^|*+?.\\") {

+ t.Skip()

+ }

_, err := regexp.Compile(regex)

if err != nil {

t.Skip()

}

compareWithGoStdLib(t, NewMyRegex(regex), regex, input)

})

}

Rinse. Repeat

Problem 4

v3_test.go:94: Mismatch -

Regex: 'Ȥ' (as bytes: c8a4),

Input: 'Ȥ' (as bytes: c8a4)

->

Go Regex Pkg: 'true',

Our regex result: 'false'

Now things are getting interesting. It seems that our regex matcher is having trouble with the non-alphanumeric character Ȥ. Let’s start with a test and go from there.

// fsm_test.go

{"multibyte characters", "Ȥ", "Ȥ"},

I’ve called this test multibyte characters because these characters are represented as more than one byte.

As we can see here, the character Ȥ is made up of the two bytes c8 and a4. If we look up c8a4 in the ASCII value table we see that it represents Ȥ. So what could be going wrong with our program?

The problem in this case is with our lexer. Here’s what we’re doing at the moment.

// lexer.go

func lex(input string) []token {

var tokens []token

i := 0

for i < len(input) {

tokens = append(tokens, lexRune(rune(input[i])))

i++

}

return tokens

}

We are looping over the bytes and converting them to runes. This means that multibyte words such as Ȥ will create two tokens; one for c8, and another for a4. This is not what we want.

Solving this is quite simple, we just need to use a range loop over the input. Go knows how to split a string into runes, which are int32 types and can support all Unicode characters. It will do so when casting a string to runes, or when using the range keyword.

For example;

fmt.Println([]byte("café")) // [99 97 102 195 169]

fmt.Println([]rune("café")) // [99 97 102 233]

So, let’s change our lexer.

@@ // lexer.go

func lex(input string) []token {

var tokens []token

- i := 0

- for i < len(input) {

- tokens = append(tokens, lexRune(rune(input[i])))

- i++

+ for _, character := range input {

+ tokens = append(tokens, lexRune(character))

}

return tokens

}

Problem 5

Mismatch -

Regex: 'B' (as bytes: 42),

Input: '̇ABA' (as bytes: 414241)

->

Go Regex Pkg: 'true',

Our regex result: 'false'

Interesting. This is similar to a problem we already solved, but with a slight variation. Here we need to find all sub-matches, not just the match from the start of the input string, but in this case we don’t need to use any of the already processed characters to make the match work.

With the test;

@@ // fms_test.go

{"substring match with reset needed", "aA", "aaA"},

+{"substring match without reset needed", "B", "ABA"},

We can solve this by removing the extra call to Next from before;

@@ // regex.go

func (m *myRegex) MatchString(input string) bool {

runner := NewRunner(m.fsm)

// for empty regex

if runner.GetStatus() == Success {

return true

}

for _, character := range input {

runner.Next(character)

status := runner.GetStatus()

if status == Fail {

runner.Reset()

- runner.Next(character)

continue

}

if status != Normal {

return status

}

}

return runner.GetStatus() == Success

}

But doing so will break the previous test. We need to reprocess the string in some situations and not in others.

Actually, there’s a better way of looking at this problem. What we actually need to do, is to check for a match against every substring of the input. We can do this by changing our matchRegex method like so;

@@ // regex.go

func (m *myRegex) MatchString(input string) bool {

runner := NewRunner(m.fsm)

- // for empty regex

- if runner.GetStatus() == Success {

- return true

- }

-

- for _, character := range input {

- runner.Next(character)

- status := runner.GetStatus()

- if status == Fail {

- runner.Reset()

- runner.Next(character)

- continue

- }

-

- if status != Normal {

- return status

- }

- }

-

- return runner.GetStatus() == Success

+ match(runner, input)

}

Ok, so far we’ve just piled everything into a new private method match, let’s build that now

// regex.go

func match(runner *runner, input string) bool {

runner.Reset()

for _, character := range input {

runner.Next(character)

status := runner.GetStatus()

if status == Fail {

return match(runner, input[1:])

}

if status == Success {

return true

}

}

return runner.GetStatus() == Success

}

This is similar to our previous implementation with one major difference: In the case of a failure, we attempt to match again on a substring of input.

// regex.go

if status == Fail {

return match(runner, input[1:])

}

This means that we will test for a match on every substring of the input.

This also means it will be a lot slower, as we now need to test for matches N times, where N is the length of the input string. For now, we’re just concerned with correctness, we can go back and optimise later, but it’s something to bear in mind.

Problem 6

Ok, we’re starting to make progress now. Let’s see our next issue.

v3_test.go:128: Mismatch -

Regex: '�0' (as bytes: efbfbd30),

Input: '̇0' (as bytes: cc8730)

->

Go Regex Pkg: 'false',

Our regex result: 'true'

This looks like an extension of the multibyte problem, so let’s add an additional test;

@@ // fsm_test.go

{"multibyte characters", "Ȥ", "Ȥ"},

+{

+ "complex multibyte characters",

+ string([]byte{0xef, 0xbf, 0xbd, 0x30}),

+ string([]byte{0xcc, 0x87, 0x30}),

+},

This time, the problem is in our match function, which takes a string and recurs on a substring.

// fsm_test.go

return match(runner, input[1:])

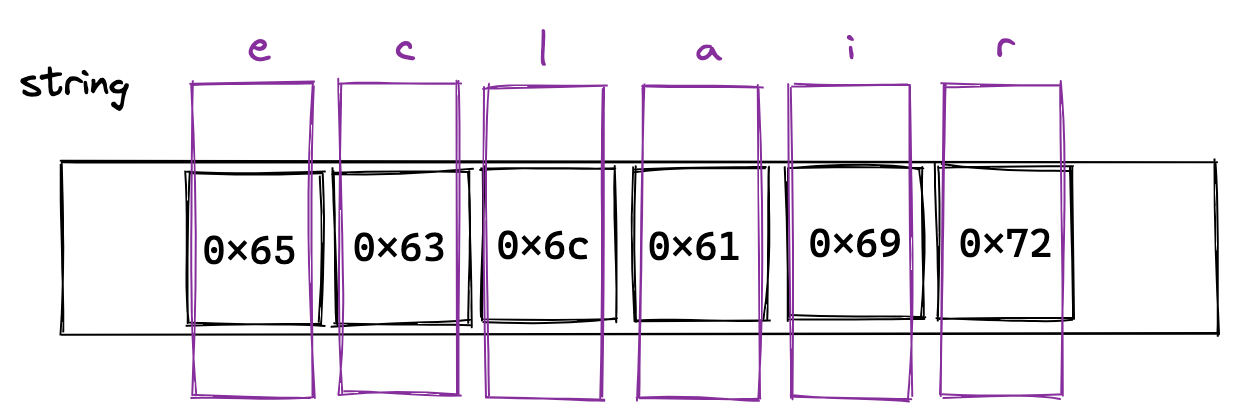

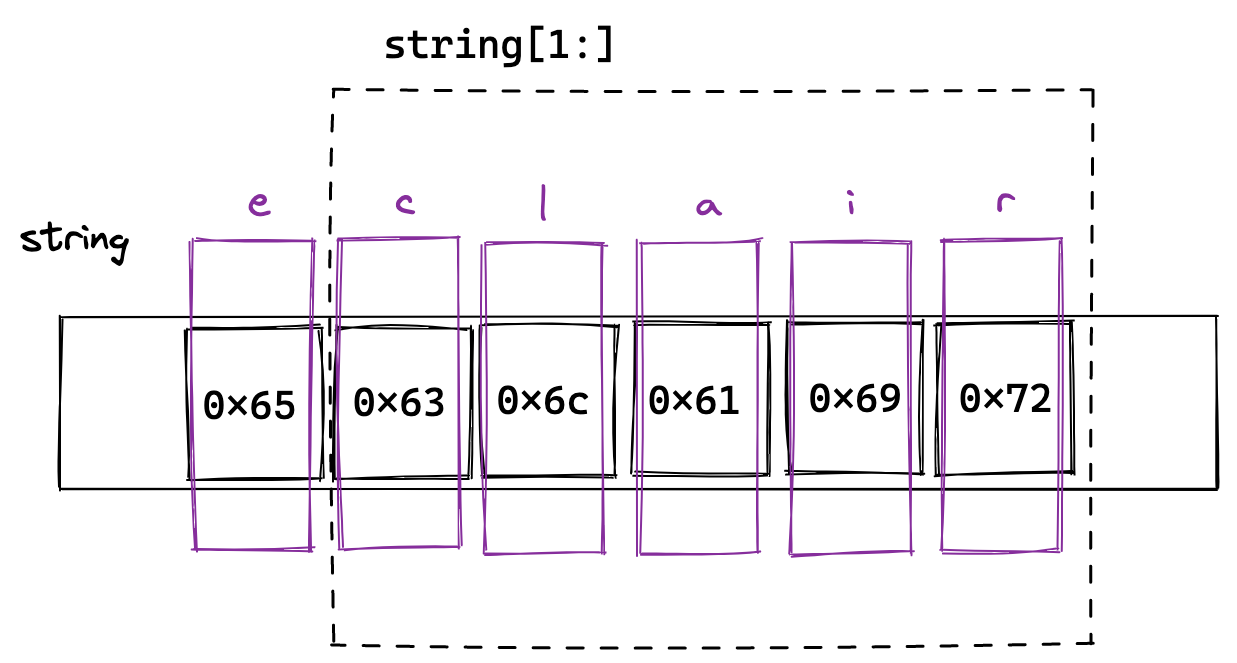

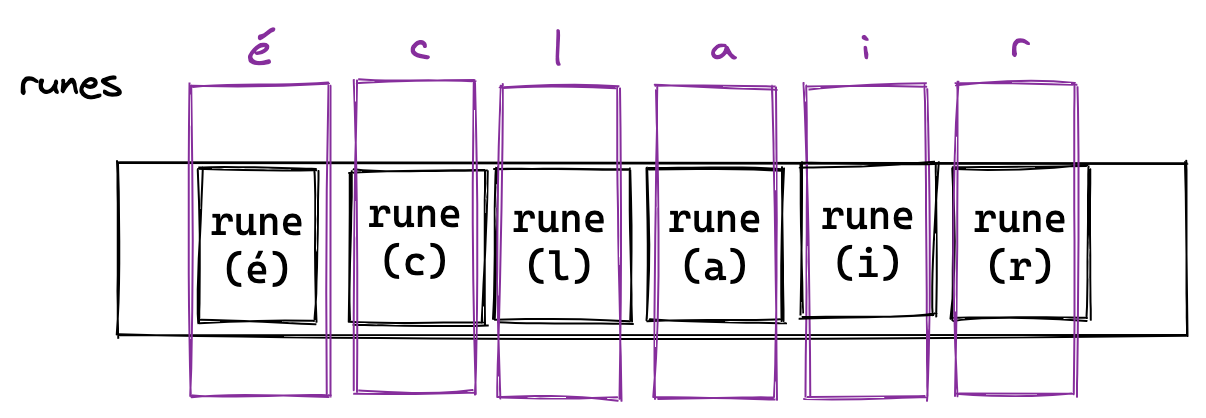

See the problem? input is a string (in other words, a slice of bytes), so we’re recurring on a substring of bytes. This is fine when each character is a single byte, but not for multibyte characters. We can illustrate this with a visualisation of the word "eclair", structured as a slice of bytes.

When we take the substring [1:] of this string, we get what we expect because we get each byte after 0x65, and so we get each letter after 'e'.

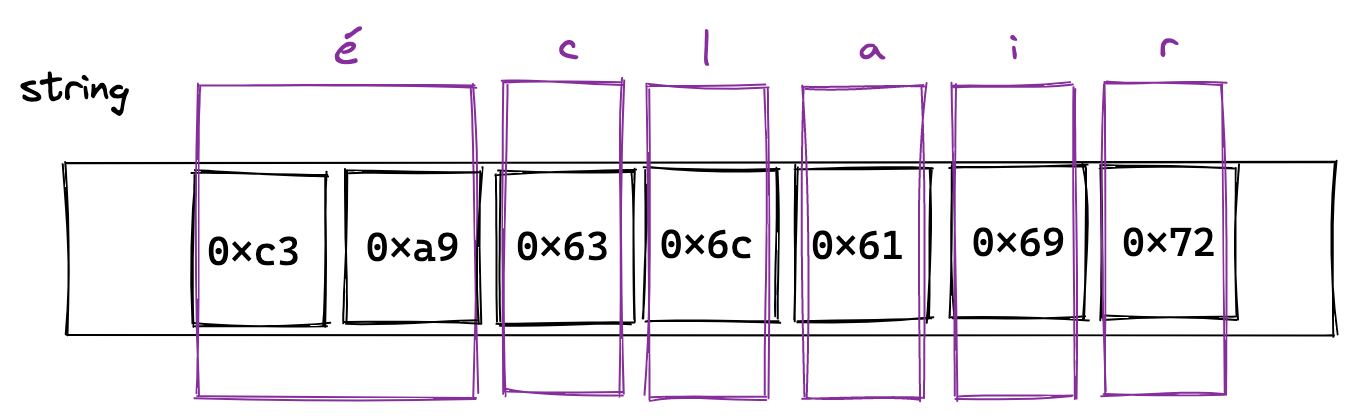

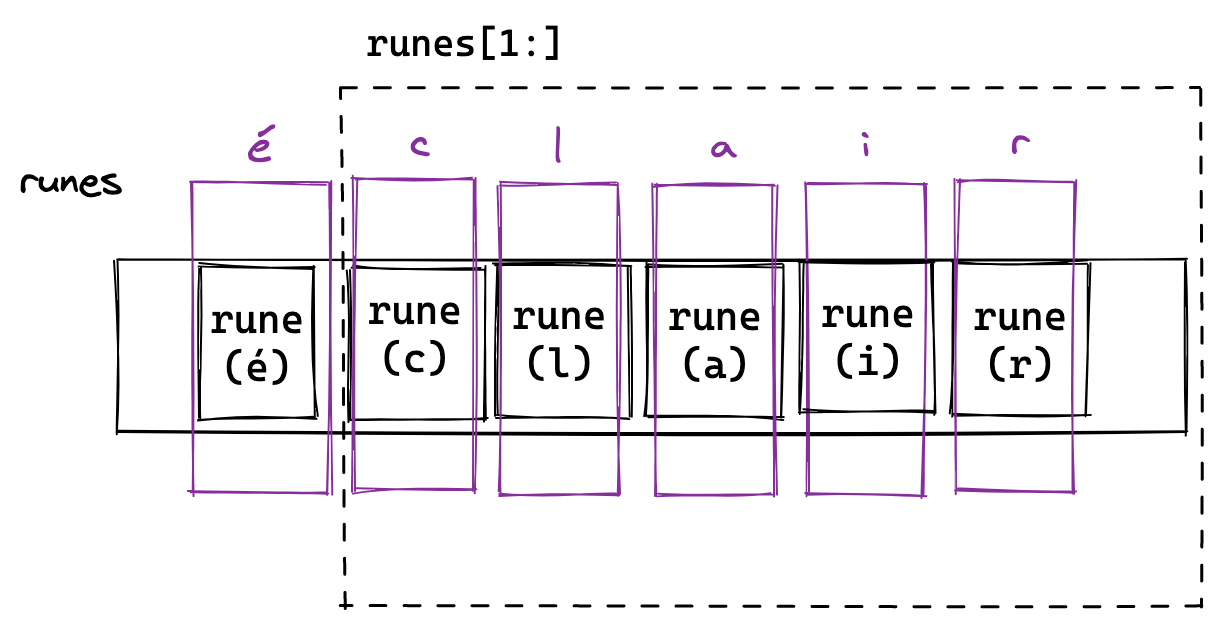

Now, let’s use the word éclair. The letter 'é' is represented in ASCII with two bytes; 0xc3, 0x19.

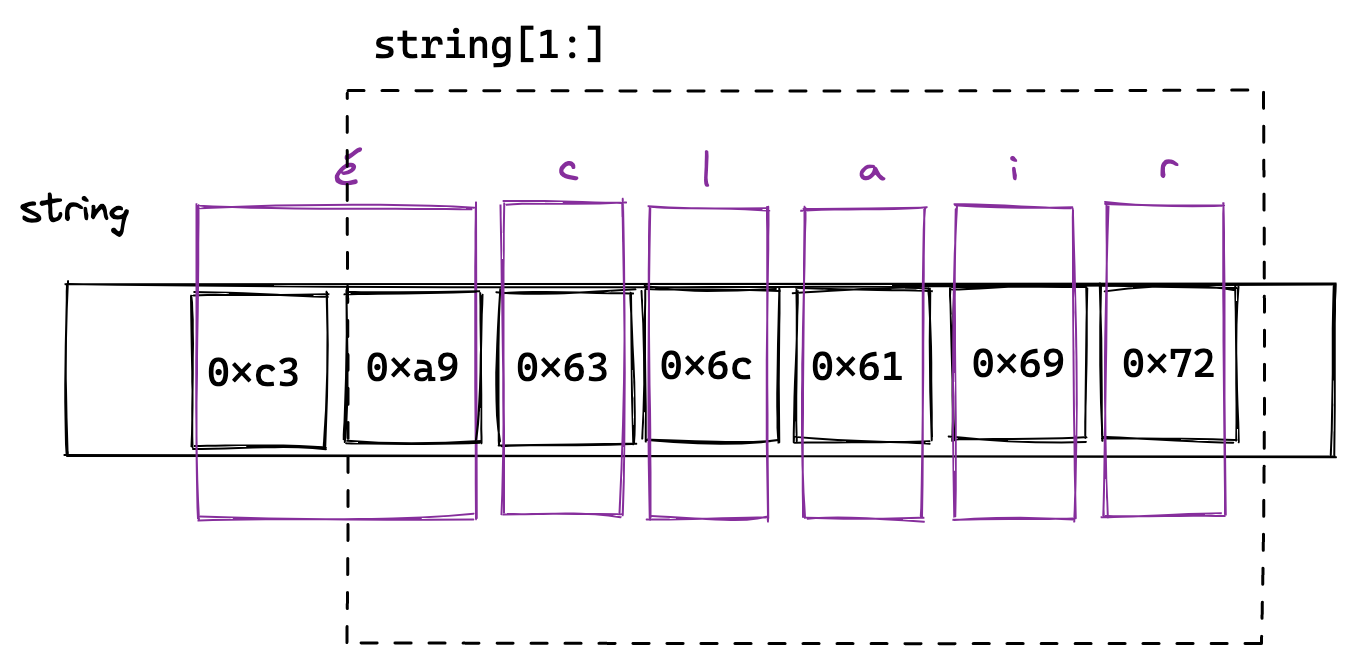

Now what happens if we use [1:] on this string…

Not good. Our 'é' character has been cut in half. This is because we’ve asked for everything after the first byte, 0xc3. Go doesn’t know that this byte is in the middle of a special character.

We can solve this using runes. Let’s see what "éclair" looks like when represented as a slice of runes.

Now, the underlying data of the characters are hidden from us. We can simply interact with them as though they are characters. So when we get the [1:] substring of this slice of runes we get:

Much better. Let’s fix this by having the function accept a rune slice instead of a string.

@@ // regex.go

func (m *myRegex) MatchString(input string) bool {

runner := NewRunner(m.fsm)

- return match(runner, input)

+ return match(runner, []rune(input))

}

-func match(runner *runner, input string) bool {

+func match(runner *runner, input []rune) bool {

runner.Reset()

for _, character := range input {

runner.Next(character)

status := runner.GetStatus()

if status == Fail {

return match(runner, input[1:])

}

if status == Success {

return true

}

}

return runner.GetStatus() == Success

}

And then, silence…

If we run the fuzzer now, we see something like this;

➜ search git:(master) ✗ go test ./src/v3/... -fuzz ^FuzzFSM$

fuzz: elapsed: 0s, gathering baseline coverage: 0/1110 completed

fuzz: elapsed: 0s, gathering baseline coverage: 1110/1110 completed, now fuzzing with 8 workers

fuzz: elapsed: 3s, execs: 481830 (160569/sec), new interesting: 0 (total: 1110)

fuzz: elapsed: 6s, execs: 1041643 (186630/sec), new interesting: 0 (total: 1110)

fuzz: elapsed: 9s, execs: 1540600 (166326/sec), new interesting: 1 (total: 1111)

fuzz: elapsed: 12s, execs: 1997730 (152333/sec), new interesting: 1 (total: 1111)

fuzz: elapsed: 15s, execs: 2593993 (198784/sec), new interesting: 2 (total: 1112)

fuzz: elapsed: 18s, execs: 3120415 (175505/sec), new interesting: 2 (total: 1112)

fuzz: elapsed: 21s, execs: 3654537 (178003/sec), new interesting: 2 (total: 1112)

Fuzzing won’t give us a green light like tests will. Fuzzing is an infinite space problem, meaning that it will never ‘finish’, but if we run it long enough we can be fairly confident that our algorithm is pretty error-proof. I let it run for a few minutes before I declared it a success.

I hope that the power of techniques like fuzzing is clear here. We’ve managed to uncover lots of subtle (and some not so subtle) bugs and issues with our code, and we’re now pretty confident that we’re providing the same behaviour as the Go regex package!

Onwards and upwards

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Our tests now look like so:

// fsm_test.go

tests := []test{

{"empty string", "abc", ""},

{"empty regex", "", "abc"},

{"non matching string", "abc", "xxx"},

{"matching string", "abc", "abc"},

{"partial matching string", "abc", "ab"},

{"nested expressions", "a(b(d))c", "abdc"},

{"substring match with reset needed", "aA", "aaA"},

{"substring match without reset needed", "B", "ABA"},

{"multibyte characters", "Ȥ", "Ȥ"},

{

"complex multibyte characters",

string([]byte{0xef, 0xbf, 0xbd, 0x30}),

string([]byte{0xcc, 0x87, 0x30}),

},

}

We’re covering a lot of cases of odd input characters, but we’re missing a lot of special characters which make regex so powerful. Let’s start adding them!

Check out this part of the project on GitHub here

Previous: 03 Starting the compiler

Next: 05 Wildcards